How early-stage founders should think about a market downturn | Advice from Chamath Palihapitiya, David Sacks, David Friedberg, and Jason Calacanis

What I Learned | Season 4, Episode 5

Welcome to all the new readers who have joined us since last month! Join hundreds of other curious readers by subscribing here:

Hey, y’all!

Happy New Year. And what a year it will be.

I will spare you from a long “How I’m doing New Year’s Resolutions” post—don’t think I didn’t think about it—and jump right into one of the things I’m focused on this year.

I’m using you (sorry!) to hold myself accountable. Because one of my goals for this year is to write consistently. I lost the habit last year, and I miss it. So, if all goes well, you’ll be seeing more of “me” in your inbox.

My plan is to write about things I’m currently learning as a startup founder.

So, if that’s not your jam, feel free to reply and say what’s up, and tell me that you’re stoked for me (even if you’re not) but since this isn’t your jam, you’ll be unsubscribing. No sweat at all. Really! I encourage constant trimming and a healthy digital diet. So, if I’m a casualty of your New Year’s digital decluttering process, that’s totally okay. Marie Kondo and I are proud of you.

Alright, enough procrastinating. Let’s get into today’s (fear-inducing) topic.

How early-stage founders should think about a market downturn

First, let’s quickly set the backstage.

1/ Epic bull run.

The market has been on an astronomical tare for the last 13 years — the biggest bull run in modern history. S&P 500 went from $770 in 2009 to $4,700 in 2021, that’s 525% or 43% a year. Unprecedented.

2/ Inflation.

Then the pandemic hit, and market volatility ensued. But, pretty quickly, the market was “up and to the right” again — after all, Twitter taught us “Stonks only go up.” This was due, at least in some part, because of the fed printing $8 Trillion. I tweeted about this in March last year. 40% of all the money supply in circulation today was printed in the last 12 months. Here is a counter-argument.

The US inflation rate rose to 6.8% in 2021, the highest since 1982.

The jury is still out on inflation. But it’s worth considering. And interest rates are near-zero still.

3/ Work-from-home boosts software.

A lot of the growth in the last couple of years was from technology stocks. Software, in particular, has done quite well. Whether that’s because these companies have become the core infrastructure for the now-here-forever trend of “WFH” aka “remote work.” Or maybe it’s just that the public markets have finally woken up to the reality that software is indeed eating the world, and SaaS companies are incredibly efficient businesses that had previously been undervalued? It’s anyone’s guess. But the fact is, the market has been roaring. Until the last couple of weeks.

4/ Dip in the last 30 days.

The market is down across the board, in the last few weeks. Even Bitcoin and crypto are bleeding out (good time to buy / not financial advice). So much for crypto being a hedge against inflation. Or maybe too soon to tell.

Public SaaS multiples are down ~30% in this latest correction — from 27.2X to 19.5X.

So, why am I telling you all of this?

Because, eventually, the music has to stop.

When? It may not be now. It may not even be this year. Maybe we’re all going to be surprised by how much more we have to go. I mean, who would have guessed we’d go this far in the green? But regardless of timing, this is absolutely a situation of “when, not if” so, why not have a contingency plan — for the inevitable when.

[All-in podcast continues to be a great listen, on many levels. It’s fascinating that four billionaires (or close enough) are able to spend a couple of hours each Friday night to hang out and talk about the latest things happening in tech, and the world. And record it for all to hear. Why would they do it? Can’t be for the money. But it does feel like a lot of eyeballs (AirPods) are tuned into it right now. And it’s a particularly fascinating demographic of listeners. Check it out if you haven’t yet.]

In this week’s podcast episode, there was one segment that was especially helpful for me, in my current startup journey. So much so, I decided to write out the text of the conversation, and put together the resources mentioned, with a bit of my own context and commentary layered in.

My hope is that it helps at least one other early-stage founder as they navigate putting together their contingency plan for the “not if, but when” of a downturn.

The quoted text is direct quotes (more or less) from this week’s episode. And of course, if you’re an early-stage founder and just want to just listen to this section of the podcast, I recommend you do so here (the segment is from 26 minutes to 60 minutes). I have cherry-picked the meat of it below and put it into text. I hope you find value in it.

What is your best advice for early-stage founders in the current environment? Assuming they have ~18 months of runway.

J. Cal posed this question to his besties. Chamath opened.

Chamath

I think Paul Graham’s advice makes the most sense here. You need to focus on being “default alive.”

Paul Graham’s essay: Default Alive or Default Dead?

Here are the first several lines of PG’s essay:

Chamath went on to talk about his experience while at Facebook and during the recession in 2008:

Here’s the thing that people don’t realize with Facebook. We were always defaul-alive. I want every single person listening to understand this. We sold poker ads for Party Poker in big banner ads on Facebook, and we made money. We were profitable!

So I don’t buy this argument of “uprofitable growth” — it is a vestige of fund dynamics and VCs who want to raise larger and larger funds to line their pockets with fees.

He closed by saying:

In 2000 you could not run an unprofitable growth business. The money would not have been there. And the real reason is, that was a market check. Meaning, you had people reallocating capital because risk-rates were different. You could put money at 6% in the US 10-year bonds.

Now, obviously you can’t do that today. So, maybe this cycle is just the new normal, and you can just always be “default dead” and be able to raise money because the incentives exist. But I wonder when that stops. I don’t know…

As a side note, Chamath referenced his 2019 Annual Letter that calls out the incredibly small amount of money raised by Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google before going public, less than $45M combined before IPO:

David Friedberg responded next with his advice.

Friedberg

#1 - Keep building. If you’re building a great business, it doesn’t matter what the market perturbations are. The market will value you at what they’ll value you. And if you’re a good business, there is going to be money available to you.

#2 - Never raise at a valuation beyond what you’re reasonably going to be able to deliver returns on at some point in the future. Otherwise, those nasty dynamics emerge. You could raise money at some crazy high valuation, that’s not always the best thing to do because then the expectation of investors coming in at that valuation is that they want to make 3x or 4x that money. And it pushes you to do something unhealthy — like bend more than you otherwise would, stretch for a bigger outcome, and put your company at risk.

So, stay focused on building your business — don’t let market conditions drive your decision-making. And second is… [then J. Cal cut him off].

David Sacks chimed in.

Sacks

I agree with a lot of what you guys have said. I believe that recessions and downturns are actually great times to build. PayPal was predominently built after the dot-com crash. Yammer was predominently built after the 2008 Great Recession. So, it’s absolutely doable.

And some things actually get easier in a downturn. There are way fewer startups getting funding, and so talent gets easier to recruit. So, things loosen up in terms of the company-building side.

The only thing that really gets harder in a downturn is fundraising. And by the way, I think it’s a good practice for [early stage] founders not to care what happens in the public markets. The only time that really touches you is when you need to access the capital markets. And then, you will be subject to the downstream impact of VCs on what’s happening in the markets.

He continued, saying:

I personally think that trying to achieve “Default Alive” status is too high a bar. I mean, it’s a wonderful thing if you can do it. Facebook and Google did it. The very best companies did it. But I know very few SaaS companies [at an early stage] that would continue to grow if they had to be cashflow positive.

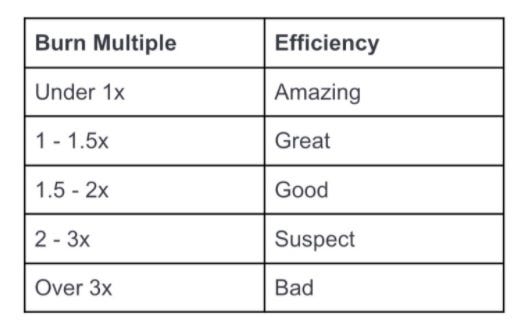

So the metric I use is “The Burn Multiple.” It’s basically “how much are you burning for every dollar of net-new ARR that you’re adding? So in other words, if you’re burning $1M over a certain period of time, in order to add $1M of net-new ARR, that’s actually pretty good. So a burn multiple of 1 or less is amazing. Even 2 is good. So in other words, if a SaaS company can add $10M of net-new ARR in a year and burn $20M, I think VCs will fund that all day long, even in a recession. But when you start getting into burn multiples of 3, 4, 5, 6, and up, that’s when VCs will think that something is wrong. It starts to raise questions about your product-market fit. Because you’re effectively spending too much money to grow. So why is the growth that hard? [Essentially, there is no market pull.]

Here is a chart from The Burn Multiple* article David wrote and referenced:

*Burn Multiple = Net Burn / Net New ARR

So in a downturn or choppy waters, you have to ‘sharpen the pencil,’ get more efficient about your burn, look at your Burn Multiple, and then, I think, if you have the opportunity to top off your ‘war chest,’ that’s smart — and don’t wait too long.

J. Cal closed out the segment.

J. Cal

And be frugal.

The amount of crazy spending I’m seeing in some startups, and unnecessary spending. If you’re spending on something and it’s not going into product, marketing, sales — you really have to ask yourself, ‘why am I spending money on going to this random conference or office space.’ Really, be frugal.

I know that when you have all this money sloshing around, you’re looking for money to spend it on. But, stay focused.

Then at minute 59 they just joke about “or you just ignore it all” and that was the end. Pretty great, honestly.

So, what should I take away as a founder?

Well, with under 18 months of runway, the gamble I’m making is that a massive correction won’t happen in 2022. But if it does, I should stay disciplined and really stick to a plan that I’ve developed ahead of time (now) to follow. It also begs the question, what are you optimizing for right now? Profit? Revenue? User growth? Depending on your answer, you should act differently as a business. And if you don’t know, you should find out. :)

At Groundswell, we’re intentionally not optimizing for profitability right now. But we are thinking deeply about monetization and the value creation (and thus, revenue) we are generating for the software companies we are going to be serving for many years to come.

Here are the two specific things I’m putting into practice after hearing the advice given in this podcast segment:

Focus less on public markets.

If something really bad happens, I’ll find out. But the often-occurring ups and downs of the standard market add an extra layer of stress that I don’t have room for, nor do I want anyway. I’m not a macroeconomist, nor should I try to become one. Again, as Friedberg advised: “stay focused on building your business — don’t let market conditions drive your decision-making.”

Don’t lose sight of the fundamentals.

“Growth at any cost” runs out. So, while the bull-run does continue to unfold—no matter for how long—a) don’t get carried away in spending and b) don’t raise on unattainable revenue multiples. Just because “you can” does not mean “you should.”

Thanks for reading and see you next time!

With humility and gratitude,

Brendan

[Written while listening to this NYE Playlist]